Most cultures have sacred and memorable sites, such as the Black Hills of South Dakota or Stonehenge. For me and many African Americans who’ve lived in Jefferson City, Missouri, one such place is The Foot. It’s more than just the convergence of two streets, Lafayette and Dunklin and the surrounding area. It was actually a repository of knowledge that has flowed like a stream to a once-thriving Black community.

Lincoln University, a cornerstone of the neighborhood, from its founding by Black Civil War veterans until at least the 1970’s, influenced its surrounding community through its diverse student body, coming from all over the country and actually, the world. A Nigerian student, courting my sister, made a dinner with fufu for my family in 1977. Chicago folks brought new ideas and styles to us. The Foot formed its own culture, quite distinct from that of the small mid-Missouri city around it.

I was six years old when we left our family farm in my uncle’s 1950 Ford to journey from Ash Grove to Jefferson City to live for a while with my maternal grandparents. As we pulled in front of my grandparent’s house, on the corner of Miller and Cherry Street, across from Donovan’s A.M.E Chapel and also the oldest Black-owned house in town (which was torn down recently to make way for an exit ramp for the freeway bisecting the community), I could hear the most beautiful carillon from Lincoln ringing throughout the neighborhood. If I’m quiet enough and concentrate, I can still hear it. In those days, it was safe enough for children to roam the streets unaccompanied. My brother Charles and I went to a actual swimming pool for the first time. There at the segregated city pool, we met a group of boys who I still think of fondly. When I was a teen-ager, the Lafayette and Dunklin intersection was a magnet that drew me up to the University’s steps. Bold old and young men gathered there, sharing folk wisdom and tales of woe.

When I hear that the few remaining houses on those once vibrant streets are in danger of being torn down, it feels as though a part of me is disappearing as well, the part that walked down Lafayette street past Wingy’s store and Mr. Johnson’s barber shop, past the hotel, where at one time Mr. “Meat” Caves made his residence. Nearby were Miss Leona’s restaurant and Mr. Turner’s gas station, and a number of beautiful two-story brick homes. There was Mr. Henderson’s cab company, which he started because often the White cabs wouldn’t deliver Black students to the University. This was a place formed before integration, where doctors and lawyers and professors lived next door to street sweepers and other ordinary blue collar workers as well as some downtrodden folk.

It seems like they’ve been tearing down this place for quite a while, but I can still hear the hot tamale man strolling along crying “Hot Tamale Hot Tamale!!” to his customers, and Dad Wesley, the produce merchant, advertising his wares displayed on a horse cart. 504 Lafayette was the home of Dr. Lorenzo Greene, the great African American historian. Mr. Charlie Robinson, a great Negro League baseball player, had a home in The Foot, as did William Ross, M.D, long time president of the local NAACP and our doctor. He was the first Black attending physician at the city hospital.

These are more than memories. They are testimonies to a vanishing culture – the self sufficient Black community, with its own professionals and merchants, a mirror of the larger society from which it was largely excluded, but complete within itself, nonetheless.

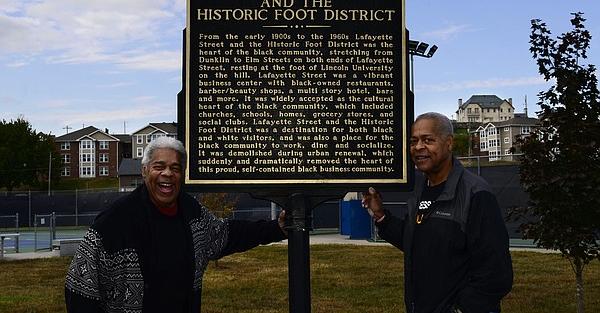

They’re putting up a plaque in Jefferson City to memorialize The Foot. Meanwhile the last remaining traces are being demolished. A way of life, and concrete evidence of its existence, is disappearing. At least two remaining houses are being threatened. How much better it would be to renovate and preserve them!

from NewsTribune.com, “The Foot named a Historic Legacy District” Anna Watson, Dec. 6, 2022